Cell-communicating ingredients are getting a lot of attention for their role in helping skin function more normally. Medical journals refer to these as “cell signaling” substances—but I think “cell communicating” is more descriptive of what they do in relation to skin care.

Where antioxidants work by intervening in a chain-reaction process called free-radical damage, “grabbing” the loose-cannon molecule that causes free-radical damage to reduce its impact on skin, cell-communicating ingredients, theoretically, have the ability to tell a skin

cell to look, act, and behave better, more like a normal healthy skin cell would, or to stop other substances from telling the cell to behave badly or abnormally. This is exciting news because antioxidants lack the ability to “tell” a damaged skin cell to behave more normally.

Years of unprotected or poorly protected sun exposure causes abnormal skin cells to be produced. Instead of normal, round, even, and completely intact skin cells being regenerated, when damaged cells form and reproduce they are uneven, flat, and lack structural integrity. As a result of these deformities, they behave poorly. This is where cell-communicating ingredients (examples are niacinamide and adenosine triphosphate) have the potential to help.

Years of unprotected or poorly protected sun exposure causes abnormal skin cells to be produced. Instead of normal, round, even, and completely intact skin cells being regenerated, when damaged cells form and reproduce they are uneven, flat, and lack structural integrity. As a result of these deformities, they behave poorly. This is where cell-communicating ingredients (examples are niacinamide and adenosine triphosphate) have the potential to help.

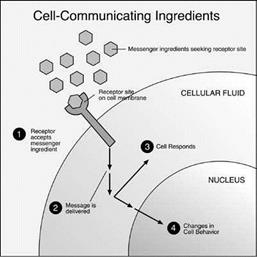

Every cell has a vast series of receptor sites for different substances. These receptor sites are the cell’s communication hookup. When the right ingredient for a specific site shows up, it has the ability to attach itself to the cell and transmit information. In the case of skin, this means telling the cell to start doing the things a healthy skin cell should be doing. If the cell accepts the message, it then shares the same healthy message with other nearby cells and so on and so on.

As long as there is a receptor site and the appropriate, healthy signaling substance, a lot of good, healthy communication takes place. But a cell’s communication network is more complex than any worldwide telephone system ever imagined. The array of receptor sites and the substances that can make connections to them make up a huge, complex, and varied group with incredible limitations and convoluted pathways that we are still finding out about. As far as skin care is concerned, it’s an area of research that is in its infancy. No doubt you will be hearing more and more about cell-communicating or cell-signaling ingredients being used in skin-care products, despite the lack of solid research. The good news is that, theoretically, this new horizon in skin care is incredibly exciting.

retinol

When it comes to cell-communicating ingredients for skin, the two we know the most about are vitamin A and niacinamide, with vitamin A (retinol is the name for the entire vitamin A molecule) having by far the most research. We know that there is a receptor site on a skin cell for a form of vitamin A called all-trans retinoic acid—also known as tretinoin. When vitamin A is absorbed into the skin it is broken down by enzymes there and becomes retinoic acid. In this form, it can send information to the skin cell telling it to behave more normally and to make healthier skin cells and, to some extent, the skin cell listens and

responds accordingly. That is what a all cell-communicating ingredients can do, especially vitamin A when it becomes retinoic acid.

Tretinoin is considered a drug by the FDA and is available in the United States and most other Western countries only by prescription. Retinol can be found in skin-care products, most typically in the form of retinyl palmitate. Retinol or retinylaldehye are considered the more active forms but they can also be more irritating. I discuss niacinamide in Chapter Fifteen, Solutions for Acne.

(Sources: International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, July 2004, pages 1141-1146; Nature Medicine, February 2003, pages 225-229; Microscopy Research and Technique, January 2003, pages 107-114; Skin Pharmacology and Applied Skin Physiology, September-October 2002, pages 316-320; Journal of Investigative Dermatology, March 2002, pages 402-408; Experimental Cell Research, March 2002, pages 130-137; and www. signaling-gateway. org.)