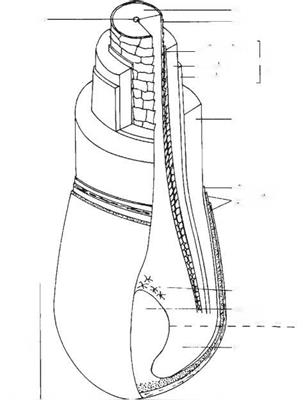

Mammalian skin produces hair everywhere except for the glabrous skin of the lips, palms, and soles. Although obvious in most mammals, human hair growth is so reduced with tiny, virtually colourless vellus hairs in many areas, that we are termed the “naked ape”. Externally hairs are thin, flexible tubes of dead, fully keratinised epithelial cells; they vary in colour, length, diameter, and cross-sectional shape. Inside the skin hairs are part of individual living hair follicles, cylindrical epithelial downgrowths into the dermis and subcutaneous fat, which enlarge at the base into the hair bulb surrounding the mesenchyme – derived dermal papilla (Fig. 1.1) [8].

In many mammals, hair’s important roles include insulation for thermoregulation, appropriate colour for camouflage [9], and a protective physical barrier, for example, from ultraviolet light. Follicles also specialise as neuroreceptors (e. g. whiskers) or for sexual communication like the lion’s mane [10]. Human hair’s main functions are protection and communication; it has virtually lost insulation and camouflage roles, although seasonal variation [11-13] and hair erection when cold indicate the evolutionary history. Children’s

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

![]()

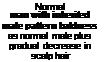

Figure 1.2 Human hair distribution under differing endocrine conditions. Normal patterns of human hair growth are shown in the upper panel. Visible (i. e. terminal) hair with protective functions normally develops in children on the scalp, eyelashes, and eyebrows. Once puberty occurs, further terminal hair develops on the axilla and pubis in both sexes and on the face, chest, limbs, and often back in men. In people with the appropriate genetic tendency, androgens may also stimulate hair loss from the scalp in a patterned manner causing androgenetic alopecia. The various androgen insufficiency syndromes (lower panel) demonstrate that none of this occurs without functional androgen receptors and that only axillary and female pattern of lower pubic triangle hairs are formed in the absence of 5a-reductase type-2. Male pattern hair growth (hirsutism) occurs in women with abnormalities of plasma androgens or from idiopathic causes and women may also develop a different form of hair loss, female androgenetic alopecia. Reproduced from Randall [221].

sexual characteristic, rather than a disorder. Marked balding would identify the older male leader, like the silver-backed gorilla or the senior stag’s largest antlers. Other suggestions include advantages in fighting, as flushed bald skin would look aggressive or offer less hair for opponents to pull [14]. If any of these were evolutionary pressures to develop balding, the lower incidence among Africans [21] suggests that any possible advantages were outweighed by hair’s important protection from the tropical sun. Whatever the origin, looking older is not beneficial in the industrialised world’s current youth-orientated culture.