Strictly in terms of the end result, there is no discernable difference in the way 3D makeup effects are created for use on the stage or screen. Though traditional stage makeup (not prosthetic makeup) is meant to be viewed from a distance, many of today’s live theater venues put actors and audience within very close proximity of one another, so makeup of any kind must read realistically from anywhere in the theater. Where the differences really begin to manifest themselves is in a particular show’s makeup budget.

Typically, theater productions have relatively tiny budgets—often barely enough to break even (or slightly better) with sold-out performances for the run of the show. Traditional stage makeup is usually an expense for each actor personally. With few exceptions, theater is not a creative outlet where one can expect to become independently wealthy over a lifetime. Actors and technical craftsmen (designers) engage in theater for love, not money. That does not mean that we are willing to lose money on the endeavor, though it does invariably happen from time to time. We accept this because we are in it for the love of the craft. Only New York’s Broadway theaters, London’s West End, and large touring Equity (Actors’ Equity in the United States and Great Britain) and perhaps a very few Equity venues elsewhere can afford 3D makeup effects on par with those regularly seen on screen.

In film and television, makeup effects are a measure of scale; in theater, they’re a measure of volume. Equity shows usually run eight performances a week for several weeks, sometimes longer. Film projects often need many days’ worth of appliances for various characters, but other factors can quickly come into play. When an actor is made up with prosthetics for the screen, it often happens early in the morning, and the actor remains made up throughout the day, touched up by the makeup artist between takes, after meals, and so on. If an appliance starts to come loose,

![]()

as they tend to do at high-movement areas such as the comers of the mouth, the camera can be cut, the appliance touched up, and then the camera rolls again.

When an actor is made up with prosthetics for the stage, it will happen as close to curtain time as possible, and if an appliance starts to come loose during a performance, there is likely to be hell to pay when the actor comes off stage! The same level of professionalism is required whether a performance is taking place before a camera or before a live audience; the stakes are immediately higher for stage productions for the following reasons:

■ There is no possibility of halting a stage performance to repair or reapply a mischievous appliance.

■ Many theaters are quite intimate, with audience members seated mere feet from the stage; if the makeup effects are not applied to perfection it will be clearly evident to those in the front rows.

■ Film and television can employ additional dialogue replacement (ADR)— rerecording dialogue by lip syncing to video playback—but theater cannot; an actor must be audibly clear and succinct throughout the theater in 3D makeup, and the visible effect of the makeup must also be as effective to people seated in the last row as it is in the first row.

Other things to take into account in creating 3D makeup effects for stage are: Is there going to be a quick change for this character, either in makeup or costume? Does the actor have to put on or take off an appliance, and if so, how long will it take? Must the actor do it alone and in the dark? If clothing must come on or off past a makeup appliance, care must be taken not to damage the makeup, or time must be factored into the change to fix any damage. If it is a two-performance day, will there be time for the actor to get out of makeup and then back into it before the second show, or will the actor remain made up during the break between shows?

Other things to take into account in creating 3D makeup effects for stage are: Is there going to be a quick change for this character, either in makeup or costume? Does the actor have to put on or take off an appliance, and if so, how long will it take? Must the actor do it alone and in the dark? If clothing must come on or off past a makeup appliance, care must be taken not to damage the makeup, or time must be factored into the change to fix any damage. If it is a two-performance day, will there be time for the actor to get out of makeup and then back into it before the second show, or will the actor remain made up during the break between shows?

Probably the biggest hurdle to overcome in creating special makeup effects for theater is cost. If you’re working on a major Actors’ Equity production, it is somewhat less a concern, but not all Equity theaters have enormous subscriber bases to allow producers to create productions from an ideal financial situation. It becomes even more of a concern with small theater companies.

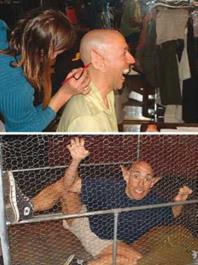

For example, special makeup effects for a Denver, Colorado, production of Bat Boy: The Musical can become a cost concern because not only must prosthetics be applied, they are not ones that can be easily self-applied, so a makeup artist must be taken into account for each performance.

Many times an appliance application can be simple enough that the actors themselves can be shown how to put them on and take them off without trouble. The "trouble" shows up in the form of having to have a fresh appliance for each performance. I have been working for several years to perfect a

method of fabricating appliances that are soft enough for an actor to create a believable performance—to emote through—yet be strong enough to be thoroughly cleaned after each performance and used many times, thereby becoming more affordable. A few years ago I created actor – applied character appliances that lasted 40 performances for children’s productions of The Garden of Rikki Tikki Tavi and Lilly’s Purple Purse.

If I can do that, I’m certain I will also be able to overcome many actors’ seeming inability to keep their dressing areas neat and organized and their makeup supplies clean and uncontaminated. But nah, I’m only human.

Lighting considerations are often different for makeup effects applications for the stage versus for the screen. Whether you’re creating prosthetic makeup for still photography, live theater, video, or film, lighting is always crucial to the way the makeup will be perceived. The biggest makeup concern from a lighting standpoint is the use of color, which is a frequent addition to theatrical stage lighting. Colored gels have a decidedly different effect on your makeup coloring—much different than under the lighting conditions in which the makeup was applied. One way to develop makeup coloration for a stage production is to equip the dressing room with the same colored gels that will be present on stage with the makeup. Another is to do a makeup test on stage under actual lighting conditions. If the effect is negative, there should still be time to suggest makeup changes. I’d try this route before suggesting that the lighting designer change her lighting plot.

Amber gels tend to flatter makeup by adding life to flesh tones. Rosco, for example, offers several shades of an amber called Bastard Amber that are quite popular; the Roscolux color range includes four useful Bastard Amber shades—#01, #02, #03, #04—and two Rose shades, #05 and #305. Another popular Roscolux color for flesh tones is Pale Apricot #304. Surprise Pink is another color that has proved very useful for flattering makeup. There are several Roscolux shades in the Surprise Pink or Special Lavender category: #51, #52, #53, and #54. The Flesh Pink filters, such as Roscolux #33, #34, and #35, enhance the effect of most makeup by reinforcing the pink tones. But be careful of some of the other "pinks." Roscolux #37, for example, leans toward lavender and tends to warm up colors in the makeup base. It may even turn cool makeup gray or blue.

Blue filters transmit little red, so red and pink makeup appears gray and "dead" under blue light. This is an important factor since makeup normally is pink or "rosy" in tone. Blue filters are important in lighting many scenes (moonlight, for example), but care should be exercised when blue light falls on the actor, since it tends to give makeup a cold look. Even greater care is necessary when the darker Rosco blues are used, since they tend to create "holes" in the facial structure, such as hollows in the cheeks. Performers should be cautioned to use rouge sparingly. You should definitely pretest makeup when blues will dominate the stage lighting.3

iwww. rosco. com/us/technotes/filters/technote_1.asp#MAKEUP.

Even rather "normal" lighting can appear to change the way makeup is seen differently by the audience than when being applied under similar lighting in the dressing room. The same production of Bat Boy: The Musical is a good example. Once the stage lighting was set, we did a makeup test under the lights, and coloring that was a perfect skin tone match under makeup lighting backstage made Bat Boy’s enormous ears look like they were glowing several shades lighter under the stage lights. We adjusted the ear color accordingly, and the results were outstanding, though under normal lighting backstage, they were much too dark. On stage, it was impossible to tell that that actor Nick Sugar hadn’t been born with those ears!

Even rather "normal" lighting can appear to change the way makeup is seen differently by the audience than when being applied under similar lighting in the dressing room. The same production of Bat Boy: The Musical is a good example. Once the stage lighting was set, we did a makeup test under the lights, and coloring that was a perfect skin tone match under makeup lighting backstage made Bat Boy’s enormous ears look like they were glowing several shades lighter under the stage lights. We adjusted the ear color accordingly, and the results were outstanding, though under normal lighting backstage, they were much too dark. On stage, it was impossible to tell that that actor Nick Sugar hadn’t been born with those ears!