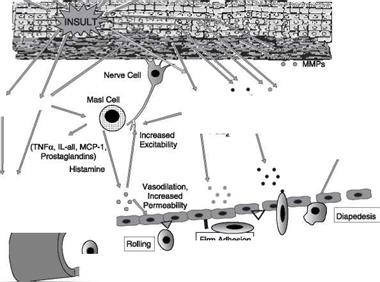

Skin inflammation, which is characterized by redness, swelling, heat, itching, and pain, can exist in either an acute or chronic form with acute disease frequently progressing to a more chronic condition. Acute inflammation can result from exposure to UV radiation (UVR), ionizing radiation, allergens, or to contact with chemical irritants (soaps, hair dyes, etc.). Assuming that the triggering stimulus is eliminated, this type of inflammation is typically resolved within one to two weeks with little accompanying tissue destruction. A chronic inflammatory condition, however, can last a lifetime, and cause considerable damage to the skin. Some of the cellular and biochemical events which occur in the skin in response to a triggering stimuli (e. g., UVR, chemical, or antigen) and which lead to an inflammatory response are shown in Figure 1. Within minutes of exposure of skin to an insult there is a rapid release of inflammatory mediators from keratinocytes and fibroblasts and from afferent neurons. In response to a triggering stimulus, keratinocytes produce a number of inflammatory mediators including PGE-2 and TNF-alpha as well as the cytokines, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8. Dermal fibroblasts also respond to the insult and to IL-1 produced by keratinocytes by increasing production and secretion of cytokines including IL-1, IL-6, IL-8 as well as PGE-2. One of the principal actions of PGE-2 produced and secreted by both keratinocytes and fibroblasts is to increase vasodilation and vascular

Lymphocyte, Г#1)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Monocyte

Monocyte

Activation f Monocytes/ Macrophages/ T-Cells

|

permeability. In addition, PGE-2 aids in the degranulation of mast cells and increases the sensitivity of afferent neuronal endings. The increased sensitivity of nerve endings by prostaglandins and cytokines results in the release of neuropeptides, including substance P and calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) (1). Neuron depolarization also increases resulting in the sensation of pain. Substance P and CGRP released by neurons, along with PGE-2, cause degranulation and release of histamine from mast cells, and they also stimulate the cell to produce a variety of inflammatory cytokines. If IgE is bound to its receptor on mast cells, exposure of skin to an IgE specific antigen can also trigger the degranulation and activation of the mast cell (2,3). Increased vasodilation and vascular permeability by PGE-2 and histamine leads to increased blood flow and extravasation of fluid from blood vessels. This causes visible redness and swelling in the inflamed area. The increased production of inflammatory mediators by keratinocytes and fibroblasts, particularly TNF-alpha and IL-1, leads to the expression of intracellular adhesion molecules, such as VCAM and ICAM, on endothelial cells of the blood vessels (4). These proteins, as well as P and E selectin, serve as anchoring elements for monocytes and neutrophils passing through the blood. The attachment of these leukocytes to the adhesion molecules slows their movement through the bloodstream and finally causes their firm adhesion to the endothelial wall (5). In the presence of chemokines, particularly IL-8 produced and released by both keratinocytes and fibroblasts, the adherent leukocytes undergo chemotaxis and migrate from the blood vessel out into the skin where they act to scavenge the area of debris and also produce additional inflammatory mediators. The initial acute response occurs within minutes of the insult to the skin and involves the production of inflammatory mediators, the degranulation of mast cells, and the vasodilation of blood vessels (6). The subsequent movement of neutrophils and monocytes into the “wounded” area typically takes up to 48 hours to occur. If the triggering stimulus is eliminated, inflammatory mediator production by keratinocytes,

fibroblasts, and mast cells ceases, the influx of leukocytes to the “wounded” area decreases and inflammation subsides.

In contrast to acute inflammation which typically resolves in one to two weeks, chronic inflammation results from a sustained immune cell mediated inflammatory response within the skin itself and is long-lasting. Antigen presenting cells (APCs) in the skin, called Langerhans cells in the epidermis and dendritic cells (DCs) in the dermis, can be activated by innate mechanisms and by exposure to the inflammatory cytokines, IL-1 and TNF-alpha, produced by fibroblasts and keratinocytes in response to a triggering stimulus. The activated APCs bind to and transport skin antigens (allergens) through the lymphatics during which time they undergo a maturation process. This maturation step allows the APCs to efficiently present the antigen to T-lymphocytes. This presentation, in turn, triggers the maturation of a specific subset of naive T-lymphocytes into memory cells and the activation of resident antigen specific T-lymphocytes. The skin-homing T-lymphocytes, which express a cell surface epitope, termed cutaneous lymphocyte antigen (CLA), migrate to the involved area of skin, and adhere to endothelial cell walls initially through an interaction between the CLA expressed on the surface of the T-lymphocyte and E-selectin expressed on endothelial cells (7). Other specific receptors on T-lymphocytes, which aid in the binding and chemotaxis of these cells into the skin, include CCR4 and LFA1 (8). Once T-lymphocyes have migrated into the skin from the circulation, they not only undergo proliferation, but also produce and secrete a wide range of inflammatory mediators as well as matrix-eroding enzymes, such as matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1; collagenase). Cytokines produced by T-lymphocytes can stimulate fibroblasts and keratinocytes to produce additional cytokines and chemokines, and can also induce the expression of a variety of tissue-destructive enzymes by fibroblasts, including MMP-1 (collagen), MMP-3 (stomelysin-1) and MMP-9 (gelatinase B). As long as the antigen or insult stimulus persists in the skin, the inflammatory response will continue, resulting in significant and serious tissue destruction (9).

Inflammatory processes in the skin, particularly those triggered by long-term exposure to solar radiation, not only cause the more obvious symptoms of redness, swelling, and itching, but also trigger molecular pathways that escalate the aging process. Actinic aging, or photoaging, that occurs following prolonged exposure of the skin to ultraviolet (UV) light from the sun results in increased cytokine production with attendant activation of genes in both keratinocytes and fibroblasts that cause erosion of the normal skin structure. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which break down the skin extracellular matrix causing sagging and wrinkling, are stimulated in sun-exposed skin. Furthermore, dermal fibroblast synthesis and assembly of collagen, which is required to maintain and restore the extracellular matrix, is inhibited while elastin production is over – stimulated, leading to elastosis. It is now widely accepted that sun-exposed skin in most individuals remains in a constant state of low level UV-induced inflammation, and that this “smoldering” inflammation is responsible for the signs of skin aging that appear in middle age (10-12).