Seasonal changes are much less obvious in human beings, where follicle cycles are generally unsynchronised after age one, except in groups of three follicles called Demeijere trios [26]. Regular annual cycles in human scalp [11-13], beard, and other body hair [11] were only recognised relatively recently.

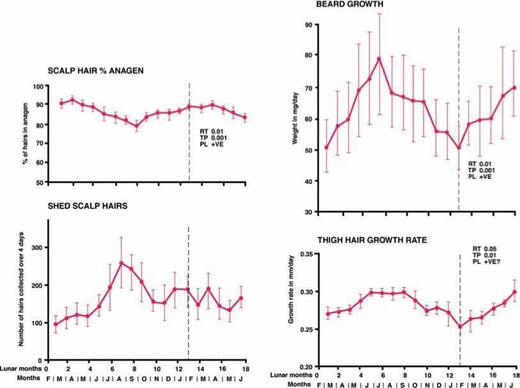

Seasonal changes in hair growth were evident in 14 healthy Caucasian men aged 18-39 years studied for 18 months in Sheffield, UK (latitude 53.4°N); these men also showed pronounced seasonal behaviour, spending much more time outside in summer, despite their indoor employment [11]. Scalp hair showed a single annual cycle with over 90% of follicles in anagen in the spring falling to around 80% in the autumn; the number of hairs shed in the autumn also more than doubled [11] (Fig. 1.6). Similar increased head-hair shedding in New York women [12] indicates an autumnal moult. Since scalp hair usually grows for at least 2-3 years [91], detection of an annual cycle indicates a strong response of any follicles able to react, presumably those in later stages of anagen.

Changes also occurred in male characteristic, androgen-dependent body hair [11]. Winter beard and thigh hair growth rate were low, but increased significantly in the summer (Fig. 1. 6). French men showed similar summer peaks in semen volume, sperm count, and mobility [130] suggesting androgen-related effects; their luteinising hormone (LH), testosterone, and 17p-oestradiol levels showed autumnal peaks. Low winter testosterone and higher summer levels were also reported in European men [131,132] and pubertal boys [133]. Testosterone changes probably alter beard and thigh hair growth rate, but they are less likely to regulate scalp follicles as seasonal changes also occur in women. However, androgens do inhibit some scalp follicles in genetically susceptible individuals causing balding [134] and dermal papilla cells derived from non-balding scalp follicles contain low levels of androgen receptors making such a response possible [135]. Annual fluctuations of thyroid hormones, with peaks of T3 in September and free T4 in October [136], could also influence scalp growth, but hypothyroidism is normally associated with hair loss [137].

In contrast to these single cycles, thigh follicles showed biannual changes in anagen, with 80% of follicles growing in May and November, falling to around 60% in March and August [11] (Fig. 1. 6).This pattern is similar to the spring and autumn moults of many temperate mammals [7] and may reflect such seasonal moulting from our evolutionary past. Presumably these cycles are controlled like those in Section 1.6.1. Human beings can respond to altered day-length by changing melatonin, prolactin, and cortisol secretion, but

|

Figure 1.6 Seasonal changes in human hair growth. Hair follicles on the scalp (left) and body (right) of British men with indoor occupations living in the north of England show significant seasonal variation. Scalp hair (upper panel) has a single annual cycle with most follicles in anagen in spring, with anagen numbers falling in autumn; the number of hairs shed (lower panel) paralleled this. Facial (upper panel) and thigh hair (lower panel) grows significantly faster in the summer months and more slowly in the winter. Measurements are mean ± SEM for Caucasian men (13 scalp and beard, 14 thigh); there is wide variation in beard heaviness in individual men [49]. Statistical analysis was carried out using runs (RT), turning points (TP), and phase length (PL) tests. Data from Randall and Ebling [11], redrawn from Randall VA [221]. |

the artificially manipulated light of urban environments suppress these responses [138]. Nevertheless, people in Antarctica [139] and those with seasonal affective disorder [140] maintain melatonin rhythms and Randall and Ebling’s study population definitely exhibited seasonal behaviour despite indoor occupations [11].

These annual changes are important for any investigations of scalp or androgen-dependent hair growth, particularly in individuals living in temperate zones. For hair loss patients, any condition may be exacerbated during the increased autumnal shedding. They also have important implications for any assessments of new therapies or treatments to stimulate, inhibit or remove hair; to be accurate measurements need to be carried out over a year to avoid natural seasonal variations.