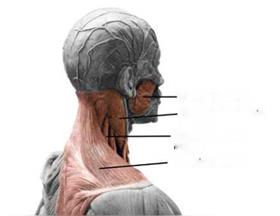

With a few exceptions, cranial muscles comprise two groups: One is located inside the head; the other connects the head to the torso. Extrinsic muscles originate at different points of the axial skeleton—at the shoulders, neck, and chest. Intrinsic muscles—the ones inside the head itself—originate and insert into the head.[8] These are the muscles that are needed for chewing, swallowing, and nonverbal communication—our ability to create various emotive facial expressions such as smiling, frowning, and grimacing.

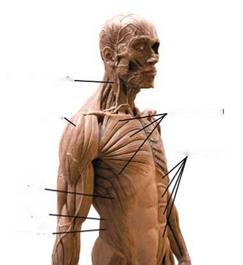

Masseter muscle

Masseter muscle

Sternocleidomastoid

Sternocleidomastoid

muscle

Levator scapulae muscle

Trapezius muscle

FIGURE 2.21

Posterior lateral view of head and neck muscles. Photo by the author. Anatomy model by Andrew Cawrse.

![]() Muscles of the face, head, and neck that could dramatically affect the physical appearance of a character makeup, the surface anatomy, are the trapezius muscle (neck), sternocleidomastoid muscle (neck), levator scapulae muscle (neck), and masseter muscle (jaw).

Muscles of the face, head, and neck that could dramatically affect the physical appearance of a character makeup, the surface anatomy, are the trapezius muscle (neck), sternocleidomastoid muscle (neck), levator scapulae muscle (neck), and masseter muscle (jaw).

THE FACE

It’s not so much the muscles of the face themselves that affect the way a character looks, though there are a few that can alter the face’s shape; it is how the muscles affect the overlying skin as the skin ages that will create alterations. (We will look at aging later in this chapter.) The muscles of the face include:

It’s not so much the muscles of the face themselves that affect the way a character looks, though there are a few that can alter the face’s shape; it is how the muscles affect the overlying skin as the skin ages that will create alterations. (We will look at aging later in this chapter.) The muscles of the face include:

■ Frontalis (epicranius) muscle

■ Corrugator muscle

■ Orbicularis oculi muscle

■ Levator labii muscle

■ Zygomaticus minor muscle

■ Zygomaticus major muscle

■ Risorius muscle

■ Depressor anguli oris muscle

■ Depressor labii muscle

■ Buccinator muscle

■ Masseter muscle

■ Mentalis muscle

■  Orbicular oris muscle

Orbicular oris muscle

■ Procerus muscle

■ Nasalis muscle

THE TORSO AND UPPER LiMBS

Muscles of the torso are divided into muscles of the thorax (upper torso or chest) and muscles of the abdomen (lower torso). Anterior (front) muscles of the chest and abdomen that are likely to affect the appearance of surface anatomy include:

■ Sternocleidomastoid muscle

■ Greater pectoral muscle (pectoralis major and pectoralis minor)

■ Clavicular part

■ Sternocostal part

■ Abdominal part

■ Deltoid muscle (anterior and medial)

■ Rectus abdominis muscle

■ External oblique muscle

■ Internal oblique muscle

■ Transverse abdominis muscle

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FIGURE 2.24

Anterior torso muscles. Photo by the author. Anatomy model by Andrew Cawrse.

![]()

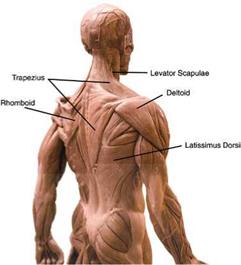

Posterior (rear) muscles of the back and lower back that are likely to affect the appearance of surface anatomy include:

■ Deltoid muscle (medial and posterior)

■ Upper, middle, and lower trapezius muscle

■ Levator scapulae muscle

■ Latissimus dorsi muscle

■ Erector spinae muscle

■ Rhomboid major and Rhomboid minor muscles

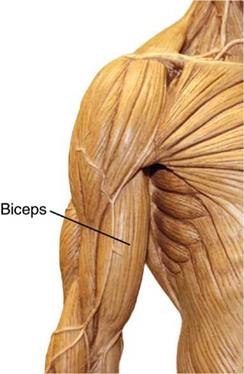

The biceps brachii is the muscle that shapes the front of the upper arm and bends the arm. The biceps is actually made up of two parts—biceps means "two heads" —that attach at separate points above the shoulder joint and converge and attach at a single point below the elbow joint.

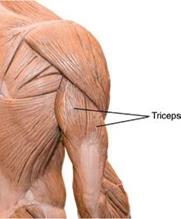

The triceps brachii—"three heads"—shapes the back of the upper arm and extends it. The three heads attach separately to the humerus bone near the shoulder joint and to the scapula and then converge into a single tendon that attaches at the back of the ulna of the lower arm.

|

The muscles of the lower arm or forearm — more than 30 of them—consist of long extensor (extending), abductor (opposing), and flexor (flexing) muscles that shape the front and back of the forearm and pass into the hand.

|

FIGURE 2.27 Posterior view showing triceps brachii muscle. Photo by the author. Anatomy model by Andrew Cawrse. |

There are no muscles in the fingers, only tendons on either side of the finger bones, wrapped by lubricated fibrous sheaths. The meaty part of the fingers is fatty tissue carrying blood vessels and nerves and providing cushion for the flexor tendons as the hand grips objects. The dorsal or back side of the hand is bony and the tendons are readily visible against the skin; the palm of the hand is more muscular. These palm muscles are enclosed by a sheet of thick connective tissue called the palmar aponeurosis. This tissue is bonded to the skin above and bones below so that the skin does not slip when the hand grasps a surface.[9]

Of the anterior torso muscles, rectus abdominis and external oblique are probably the most recognizable muscles, next to pectoralis major. Well-defined rectus abdominis is the classic washboard "six-pack" abdomen we’ve all seen on body builders.

The hip and thigh bones of the lower extremities are surrounded by some 27 muscles, comprising extensor, adductor, rotator, and flexor muscles. These large, powerful muscles are the ones that enable us to stand from a seated position, supporting almost our entire body weight. Surface definition of these muscles is frequently greater in men than in women.

Quadriceps femoris muscles flex the hip joint and extend the knee; as the name implies, it is a four-part muscle, made up on vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, vastus intermedius, and rectus femoris, that begins at the front and side of the femur near the hip joint and at base of the spine; these components converge into a single tendon that covers the knee (patella) and attaches at the head of the tibia bone, at the top of the shin. The quadriceps (vastus lateralis) and body fat beneath the skin’s surface shape the outside of the thigh, while rectus femoris shapes the front of the thigh. Sartorius, the longest muscle of the human body, is both a flexor and an adductor and separates the quadriceps from the thigh’s adductor muscles; it bends the knee and pulls and rotates the thigh.

The back of the thigh is shaped by the semi-tendinosus and biceps femoris muscles.

Both muscles attach near the head of the femur and insert, or end, at the head of the fibula in order to be able to flex the knee joint and extend the hip. Gluteus maximus is the large muscle of the buttocks; it extends and rotates the hip laterally. The buttocks are shaped by the gluteus maximus and by fatty tissue that covers it beneath the skin.

![]()

The bones of the lower leg and foot are accompanied by more than 30 muscles; the muscles of the lower leg are arranged in two sections, one anterior on the outside of the shin and the other

posterior, giving shape to the calf.11 These muscles are separated by the lower leg bones, the tibia and fibula. These muscles are responsible for our ability to draw our foot back, point it down, and turn it inward or outward. Tibialis anterior is a strong, tapered muscle that shapes the front of the leg to the outside of the shin (there is a ridge that runs along the anterior shaft of the tibia).

![]()

The tibialis anterior narrows into a tendon that passes over and under the instep of the foot, allowing us to flex it tightly, pull the foot back, and/or turn it inward. The superficial muscles of the posterior of the lower leg—soleus, planta – ris, and gastrocnemius—shape the back of the calf; these muscles share a common tendon, the calcaneal tendon, better known as the Achilles tendon, which is a short, thick tendon that is clearly visible at the back of the foot as it attaches onto the upper back of the heel bone (calcaneus).12

|

|

Similarly to the muscles of the hand, the muscles of the foot are mostly beneath, on, or inside the sole. They act on the toes to collectively spread them, draw them together, pull them back, or curl them under. The sole is covered with a plantar

“Sarah Simblet, Anatomy for the Artist (DK Publishing, 2001). 12Sarah Simblet, Anatomy for the Artist (DK Publishing, 2001).

aponeurosis in tandem with the deep fascia pad of the foot. Just like the hand’s palmar aponeurosis, it protects the foot, gives attachment to the foot muscles, and holds the skin of the foot firmly in place so that it does not slip as we stand or walk.[10]