"Plus Qa change, plus c’est la meme chose." The more things change, the more they remain the same. These words, attributed to French journalist and novelist Alphonse Karr from Les Gruepes in 1849, could hardly be more accurate in describing the business of special makeup effects today. Despite enormous advances in CGI technology (take a look at the makeup effects in The Exorcism of Emily Rose, for example: extensive digital makeup effects, very little of it practical), the majority of makeup effects work in motion pictures is still very physical. Makeup effects for theater are practical by necessity; there can be no digital enhancement before a live audience. In fact, once a practical effect becomes digital, it is referred to as a visual effect, not a special effect. However, a great deal of design is being done digitally, which we discuss in the next chapter. In motion pictures and television, a significant amount of work is beginning to be done through the use of digitally compositing elements of computer-generated imagery

![]()

(CGI) with live-action footage. It can be a very effective combination, especially when you realize you can only add, not take away, with makeup appliances. An outstanding example of practical makeup effects with digital accompaniment can be seen in The Mummy (1999) as the High Priest Imhotep, played by Arnold Vosloo, begins to regenerate.

It certainly hasn’t always been that way, but inventive, innovative, creative people have been fooling the eye with special effects and special makeup effects since before the advent of moving pictures in the 1890s. There are scads of books and web sites in which you can find ample history of film, theater, stage craft, special effects, and special makeup effects, so this chapter doesn’t present a history lesson. But a few pioneers are worth at least mentioning; their contributions to our industry and our craft have been monumental.

Arguably the first great master of special makeup effects was actor Lon Chaney, who designed and applied his own makeup in the horror classics The Phantom of the Opera (1925), The Unknown (1927), and The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923). Many years later, Academy Award winner Dick Smith, the recognized father of multipiece overlapping appliances, created the 121-year-old Jack Crabb for Arthur Penn’s Little Big Man (1970), starring Dustin Hoffman as Jack Crabb. The makeup was created out of foam latex and comprised 14 separate pieces, including hands and eyelids. Almost four decades later, Smith’s process of multiple overlapping appliance pieces is still the industry standard for applying complex makeup, whether in foam latex, gelatin, or silicone. It has since been adopted by and improved on by the likes of Neill Gorton (Doctor Who, Children of Men), Stan Winston (Edward Scissorhands, Terminator 2), David Elsey (Farscape, Star Wars: Episode III—Revenge of the Sith), Rick Baker (An American Werewolf in London, Planet of the Apes), Mike Smithson (Spiderman 3, Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me), Ve Neill (Pirates of the Caribbean I, II, and III, Beetlejuice), Greg Cannom (Van Helsing, Mrs. Doubtfire), Matthew Mungle (Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World), Bill Corso (Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events, Galaxy Quest), and many other truly remarkable makeup artists.

Neill Gorton owns and operates Neill Gorton Prosthetics Studio and Millennium FX Ltd. in the United Kingdom, providing special makeup effects, prosthetics, animatronics, and visual effects for films, TV, and commercials worldwide. He is also the man responsible for creating the amazing creatures seen in the BBC’s Doctor Who since its distinctive 2005 rebirth. Neill’s impressive credits include Saving

Private Ryan, Gladiator, Tomb Raider (I and II), The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Sahara, and Children of Men. Neill has been an enormous help and encouragement to me and has influenced how I approach almost everything I do in this field.

In Neill’s own words, “Not many 12-year-olds know what it is they want to do with their lives and eventually

|

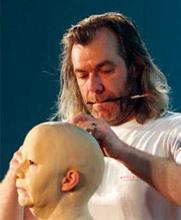

FIGURE 1.1 Neill applying one-piece silicone age makeup to Karen Spencer. Photo by the author. |

succeed at it. Frankly, I’m a bit of an oddity, and at the age of 12 I was already planning my career.” This was in a suburb of Liverpool long before anyone had even heard of the Internet. Neill scoured magazines and books for any snippet of information that would help him achieve his goal. At age 15 Neill was already working with a mask maker in London; by 17 he was working on his first motion picture.

Like many artists working in the field of special makeup effects, Neill was influenced by the stop-motion animation

of legendary special effects pioneer Ray Harryhausen. Ray created animated model monsters and dinosaurs for films such as Jason and the Argonauts, Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger, and Clash of the Titans. At about the same time that Neill was learning about Harryhausen’s groundbreaking work, films such as Star Wars and ET were bringing more lifelike monsters and aliens to the screen through ani – matronics and prosthetic techniques.

So Neill’s attention turned from creating miniature monsters in clay to full-size mechanical beasts and prosthetic makeup. His very understanding parents realized how passionate he was and encouraged his new “hobby.” By this time he’d been communicating with a number of makeup and special effects artists by post and received varying advice. Neill says, “Ultimately it watered down to ‘Do practical subjects,’ so amongst others I chose art, photography, and craft design and technology, which was an amalgam of metalwork, woodwork, and technical drawing.”

“Looking back, craft design and technology was one of the better choices I made, because it taught the process of breaking down a product using a basic brief to determine design and function, following through to construction using a variety of skills and materials. All these things are very much a part of the work I do today, and this class gave me the fundamental skills to ‘deconstruct’ a project into its salient parts and follow it through from beginning to end.”

|

|

|

In addition, Neill also studied drama because it gave him more time to experiment with makeup and his artistic skills to see how that role could affect the “other side of the curtain”—how the final performance is perceived by an audience.

“The last piece of the puzzle was chemistry,” says Neill. “A special effects man working at the BBC, whose name, sadly, I forget, had kindly written a reply to my young enquiry telling me that chemistry was an important science in this area of work, and I’m grateful to him because he was right. I work in a world dominated by monomers, polymers, and polyesters, endothermic reactions and exothermic reactions, alkalines and solvents. My chemistry skills aren’t first rate, but I learnt enough not be totally bamboozled when a rep from a chemical supply company starts waffling on about polymeric chains.”

As a consequence of Neill’s persistent contact with and approaches to the industry practitioners of the time, he was offered a couple of weeks’ work with a makeup artist by the name of Christopher Tucker. Neill had communicated

with Chris for a couple of years via post and had visited him at his studio the previous year and shown him some of his work. The offer was to come and assist for a couple of weeks working on another theatrical production and helping cast prosthetic appliances for the West End theatrical production of Phantom of the Opera makeup.

Neill’s expertise in the field has taken him all over the world, and his travels are far from over. Neill says he wouldn’t change his career path for anything, but adds, “Were I to be starting out all over again today, finding a proper vocational course in screen prosthetics which fully prepares you for a career as a workshop technician or enhances your skills as a prosthetic makeup artist for onset work would be like manna from heaven and make the path into the industry so much easier to navigate. Hence the reason for having set up my own training studio for others who want to follow in my footsteps, but with a little less time wasted in wondering which way to turn next and bickering with well-intentioned but curriculum-bound college tutors along the way!”

|

|

||

The very first Academy Award for makeup was given to MGM Makeup Department Head William Tuttle in 1964 for his landmark work of transforming Tony Randall in The Seven Faces of Dr. Lao, though Tuttle’s work was hardly the first notably brilliant makeup since Lon Chaney’s self-applied creations some 40 years earlier. The list of remarkable, memorable makeup work continues to grow with each passing year, but some have become indelibly etched in our collective consciousness (in

no particular order): Jack Pierce’s work on Boris Karloff as Frankenstein’s Monster in Universal Pictures’ Frankenstein (1931); John Chambers’ extraordinary work in 20th Century-Fox’s The Planet of the Apes (1967); and Jack Dawn’s Tin Man, Scarecrow, and Cowardly Lion for MGM’s The Wizard of Oz (1939). A list of cool and favorite makeup could be as long as this book, and if you asked 30 artists for lists of their top 10, you’d probably get 30 different lists.

|

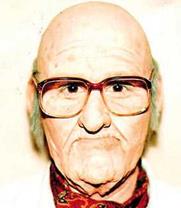

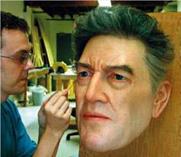

FIGURE 1.6 Jamie detailing a portrait of Chris (MEFIC Collection, Spain). Image reproduced by permission of Jamie Salmon. |

Jamie Salmon is a British-born contemporary sculptor living in Vancouver, British Columbia. He specializes in photorealistic sculpture, utilizing materials such as silicone, rubber, fiberglass, acrylic, and human hair.

The themes of Jamie’s works are varied. He says, “I like to use the human form as a way of exploring the nature of what we consider to be ‘real’ and how we react when our visual perceptions of this reality are challenged. In our modern society we have become obsessed with our outward appearance, and now with modern technology we are able to alter this in almost any way we desire. How does this outward change affect us and how we are perceived by others?”

Every piece of work that is created in the studio is the result of a painstaking, multistage process that is both artistic and technical. It can take anywhere from several weeks to sometimes months to create a piece, depending on its complexity and scale.

Jamie’s work can be seen on permanent display in the MEFIC collection, which opened in early 2008. MEFIC is a contemporary sculpture museum showcasing work from some of the world’s most influential modern contemporary artists.

Oxford art historian Steve Pulimood has written of Jamie’s work, “From Picasso to Freud, painting the human form remains entrenched in the history or art making. Every foundation art education requires time with a model, and even

|

|

self-trained artists of masterful figuration, including Francis Bacon, no matter how fervently they denied the fact, took pencil to paper and improved with age. Giacometti, arguably the 20th century’s most important sculptor of the human body, understood that timelessness could be represented in its gaunt essential form. Jamie Salmon works in a long tradition that extends from Franz Xaver Messerschmidt (1736-1783) to Ron Mueck (b. 1958). Messerschmidt was born in the age of enlightenment, when the physiognomy

of the face and its extreme expressions were a science. Salmon’s bronze offers to the viewer a fragmented stoicism, a portrait bust of statuesque vulnerability.”

In Mueck, Salmon has a peer in modern medium and intent. Salmon has replicated the visage of the filmmaker David Lynch, earmarking a mascot for the strange, disturbing, and quietly uncanny.”1

However, Jamie is more than just an incredible sculptor of larger-than-life realism. He is also an accomplished makeup effects artist whose film work includes Freddy vs. Jason, Final Destination 2 and 3, Scary Movie 4, The Fog, X-Men: The Last Stand, Snakes on a Plane, Fido, and The Wicker Man.

|

FIGURE 1.10 Director David Lynch. Image reproduced by permission of Jamie Salmon. |

‘Steve Pulimood, the Saatchi Gallery, www. saatchi-gallery. co. uk, posted by editorial on August 31, 2006.

Within the industry there is some confusion about boundaries; when do special makeup effects stop being makeup, per se, and become special effects (which includes puppetry and animatronics) or the domain of prop designers? Is a severed head made from a lifecast of the lead actor’s head and whose eyes blink and neck bleeds a makeup effect, special effect, or a prop? It depends on whom you ask, I guess. Legendary makeup effects pioneer Vincent J-R Kehoe said that though special makeup effects are character work in makeup, they belong to a specialized niche within the industry because creating makeup effects requires skill in painting, sculpting, mold making, and casting as well fabricating electronic controllers and articulated figure armatures used in animatronics. Therefore, he said, the work is not just makeup, but also special effects manufacturing.[1] And the field draws not only graduates from art schools but from the fields of engineering, industrial design, chemistry, and medicine as well. In fact, a cross-over between the worlds of makeup effects and the medical fields is involved in the creation of facial and somato (body) prosthetics.